Introduction

On a weekday morning, the carpenter from Nazareth spoke in the dust and din of the marketplace. His words were plain, stories of farmers and fishermen, all in the rough-hewn accents of Galilee. But on the Sabbath, Jesus stepped into the synagogue and something changed. He was handed the scroll of Isaiah and He read in the sacred tongue of Scripture, Hebrew, not the Aramaic of the street.

The scene is striking: the same voice that spoke of lilies and sparrows in village lanes now resounds with “The Spirit of the Lord is upon Me” in the venerable cadences of the prophets. Christ knew the difference. There is a language of the common crowd, and there is a language of the sanctuary – a language offered up to God. Even as Jesus taught in ordinary speech to reach ordinary people, when He worshiped, “as was His custom,” He entered the realm of sacred speech

This distinction is not born of snobbery or superstition. It is woven into the fabric of biblical faith. In ancient Israel, God’s people heard Hebrew in the temple and synagogue – the language of Scripture and prayer – even while they spoke Aramaic at home. A passage in Nehemiah describes the law being read aloud in Hebrew and then explained so the people could understand (a translator giving the sense), hinting at a sacred tongue set apart for God’s Word. In the New Testament, we find Jesus participating in this practice. Luke records Him standing to read Isaiah in the Nazareth synagogue

The very act speaks volumes: worship lifts us from the street to a place patterned after heaven. In the book of Revelation, John beholds worship “in spirit” and sees that heaven’s worship is a royal ceremony, not a casual circle. Elders and angels cry “Holy, Holy, Holy” in thunderous reverence, and the saints are arranged around a throne

Earthly liturgy, Scripture shows, is meant to be a reflection of that heavenly reality, a “pattern” shown to us so that, for a time, we might leave the world’s profane chatter and join the language of angels.

Approaching the King: Sacred Speech in History

When the earliest Christians gathered on the Lord’s Day, they understood that they were stepping out of ordinary life into a sacred story. Justin Martyr, writing around A.D. 150, gives us a window into a Sunday assembly. “On the day called Sunday,” he writes, “all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read”

After the reading, a sermon of exhortation would follow, then prayers, and finally the Eucharistic meal

This was no mere casual meet-up or marketplace chat; it was a ritual of Word and Sacrament, a formal encounter with the divine King. The early Christians, many of them humble folk – slaves, merchants, laborers – nonetheless lifted archaic-sounding words of Scripture and prayers to God with one voice, saying “Amen” together at the end

In a world where Latin, Greek, and Aramaic intermingled, the Church wove a tapestry of praise from whatever language best conveyed reverence. They even carried over certain Hebrew words unchanged – “Amen, Alleluia” – treating them as precious gems that should not be recut.

The Church Fathers understood that the speech we direct to God ought to be special. Origen, in the third century, mused on Paul’s teaching that we must pray “as we ought.” Origen explained that this involved two dimensions: the heart of the one who prays and the language used in prayer.

In other words, even that early in Christian history, it was acknowledged that some words befit the glory of God more than others. Origen knew what every child senses when attempting to speak to the Almighty – that feeling that one’s everyday words are insufficient for so great a task. St. Augustine too, bishop of the bustling city of Hippo, was surrounded by the common Latin of the streets, yet in church he was steeped in the lofty cadences of the Scriptures and ancient hymns. It was Augustine who said that when we sing to God, we pray twice – and indeed he wept upon hearing the sanctified singing of the Milanese congregation, for the beauty of their liturgy pierced his heart. He preached and taught in Latin, yet often quoted from the Greek Bible and the old Latin Psalms, drawing on tongues older than his own day.

. The voices of antiquity echoed in Augustine’s cathedral, just as Hebrew echoes in the chants of a Latin Mass, or Greek in the Kyrie of an English prayer service. Across the ages, the Church has always adorned her praise with echoes of yesterday’s language – not to alienate her children, but to remind them they are part of a story far bigger than the present moment.

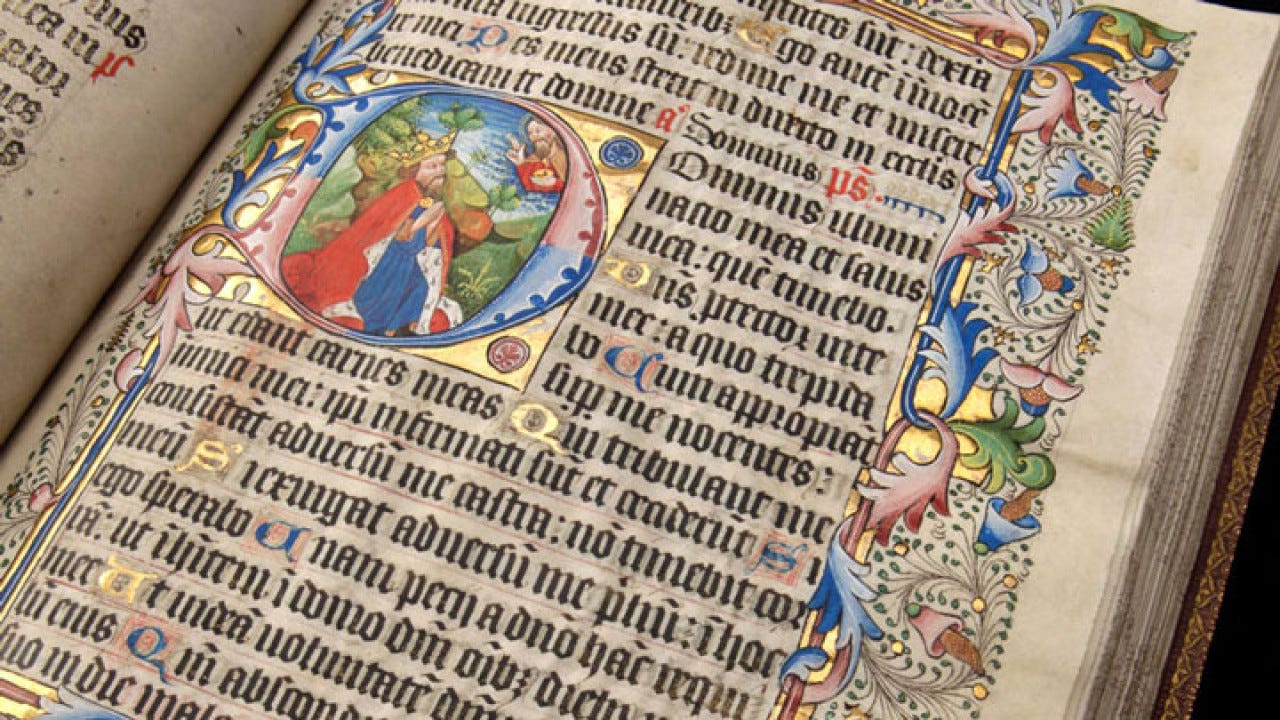

Even in the synagogue before Christ, there was a reverence for language. A devout Jew might converse in Aramaic at home but would hear the holy Scriptures in the classical Hebrew of Moses and David. This was not hypocrisy; it was holiness. It was an understanding that some words, by long use in worship, become saturated with the divine presence. They become like cherished heirlooms in the family of faith – handled with care, polished with use, set apart for sacred moments. When the reader in a first-century synagogue unrolled the scroll to proclaim “Hear, O Israel…”, he spoke in the tongue of Scripture, and all listened in awed silence. Then perhaps an interpreter would paraphrase the reading in the common tongue so all understood. But the reading itself remained in the sanctified language, as if to say: These are not just anyone’s words; these are God’s words. Likewise, the early Christians, even as they quickly translated the Bible and liturgy into new vernaculars for new peoples, still retained a sacred register. As one scholar observes, from the time of Christ onward “churches have tended to worship in language that is older than what is spoken in everyday settings.” Early believers heard the Psalms in a “classical” style of Hebrew or Greek, Augustine preached from Bible translations centuries old, and later the Latin Vulgate itself grew archaic with time – yet was lovingly kept in use.

There’s a continuity here: a sense that in approaching the King of the Universe, one does not use the same tone as haggling in the market.

We approach the thrice-holy God as Isaiah did, with trembling lips that cry “Holy!” – a word spoken in Hebrew in Isaiah’s vision and still sung in Latin as “Sanctus!” or in English as “Holy!” by Christians today. Different languages, one reverence.

Reverence and Reform: From Cranmer to Calvin

In the 1500s, the Protestant Reformers faced a church that had become foreign to its own flock. In Western Europe, worship was conducted almost entirely in Latin, a tongue most ordinary people could no longer understand. The Reformers’ cry was not against sacred language per se, but against an untethered tongue that left God’s people in ignorance. Thus Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, took the worship of the English church and gave it back to the people in their mother tongue.

With the Book of Common Prayer, first published in 1549, every ploughboy and milkmaid could hear and speak prayers in English for the first time. This was revolutionary – “prayers in their own language for the first time in history!” one historian exults.

No more mumbling of mysterious Latin phrases without comprehension. Now the farmhand in the field and the lord in the manor could kneel side by side and say “Our Father” and “Give us this day our daily bread” in a tongue understanded of the people.

Yet here is the wonder: Cranmer’s English was no crude, workaday speech. It was English measured and cadenced to sound like the language of Scripture and ancient devotion. Phrases from the Bible poured into the Prayer Book, shaping its rhythms: “with this ring I thee wed,” “earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust,” “in sure and certain hope of the Resurrection.” It was the language of the common folk, yes, but raised to a poetic beauty. In fact, so resonant were Cranmer’s prayers that they have molded the English language itself – after the Bible, the Prayer Book is the most frequently quoted book in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.

The Reformers believed every people should worship God in a voice they comprehend – Article XXIV of the Articles of Religion flatly states that praying or administering sacraments in an unknown tongue is “plainly repugnant to the Word of God”.”

But crucially, “understood by the people” did not mean indistinguishable from common chatter. It meant the meaning should be clear – the mystery of the faith should shine through unhindered – not that the style should be pedestrian. John Calvin in Geneva likewise aimed for simplicity and clarity in worship, stripping away frivolous pomp. But Calvin also insisted on reverence. He wrote that when we come to God in prayer, “let the first rule be to have our hearts and minds framed as befits those who are entering into conversation with God.”

We lay aside “carnal or earthly thoughts” that cling to us.

In other words, we consciously shift registers: we remind ourselves we have an audience with the King. Calvin even uses a courtly analogy – if you had a private audience with a monarch, would you fiddle with your to-do list or speak carelessly?

Certainly not. You would choose your words and actions with care. So too in worship: our outward speech and posture help frame an inward reverence.

The Reformers, then, gave us worship in our own languages, but they did not abandon the idea of a sacred register. Consider the King James Bible of 1611. It was written in English, for English speakers – yet the translators intentionally chose a slightly archaic, elevated style, even in their own day. In fact, the King James Version (and the contemporaneous Anglican liturgy) “was intended to be old-fashioned on the day it was published.”

Phrases like “How great Thou art” and “hallowed be Thy name” were crafted to resonate with the reverent “thickness” of older forms

This was not nostalgia. It was a conscious decision that holy things benefit from a venerable tone. There is, as one Anglican writer puts it, “nothing inherently valuable” about saying “Thou” instead of “You.” God understands every language, every dialect, even the inarticulate groan. Yet, over time, the Church found good reasons to be conservative in liturgical language

First, because the very words of Scripture and the apostles are treasures – translating them too freely or into fleeting slang risks losing richness. It’s why to this day we still say “Amen” and “Alleluia” (Hebrew words) and “Kyrie eleison” (Greek for “Lord, have mercy”) in services across the world. These words have traveled unchanged from Hebrew into Greek into Latin into English, like golden threads running through successive tapestries of worship.

Second, the Church has learned by long experience that familiar sacred words carry a weight of glory, meaning they have proven their fitness in speaking to the Holy One

We inherit them the way a young knight might inherit his grandfather’s well-worn armor, trusting that these phrases, hallowed by use, can bear the weight of divine address. And third, preserving a sacral mode of speech links us to our forebears. It creates continuity – a rich network of connections, as if our words echo in the stone vaults of a cathedral, reverberating with the prayers of generations before.

None of this was about elitism for the Reformers. Cranmer’s English prayers were intended for ploughmen and princes alike. The very name “Common Prayer” means it was prayer held in common, shared by all. The Reformers’ drive to translate worship was a drive to include more people, not fewer. And in our own day, when some say that the old liturgical English is too archaic for ordinary folks, it’s worth remembering that for centuries ordinary folks – with far less education than today – prayed and sung with those very words and found them to be a wellspring of understanding. A milkmaid in 17th-century England might not know how to read, yet she knew by heart the words “We have erred and strayed like lost sheep” and understood their truth in her soul. Reverent language was not a barrier, it was a bridge – a bridge between earth and heaven, between present and past, between a poor sinner and the Majesty on high.

Language of the Numinous: Lewis and Tolkien

No one understood the power of sacred language and ritual better than the 20th century’s great literary theologians, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Both men witnessed a time of rapid change in the church’s worship, and both, in their own way, pushed back against the flattening of the numinous. Lewis, though a layman, was a keen observer of liturgy. He warned against the incessant drive for novelty in worship – “incessant brightenings, lightenings, lengthenings, abridgements…” – because he knew it distracts from the whole point of worship.

In one of his letters, Lewis offers a beautiful analogy He wrote:

“Every service is a structure of acts and words through which we receive a sacrament or repent or adore. . . It works best. . . when, through long familiarity, we don’t have to think about it.”

In other words, as long as you’re noticing the steps of a dance, you aren’t dancing – you’re still learning the steps. “A good shoe is a shoe you don’t notice,” Lewis explains.

“Good reading becomes possible when you need not consciously think about the letters or spelling. The perfect church service would be one we were almost unaware of; our attention would have been on God.”

What does this have to do with language? It means that the register of our worship should be stable and rich enough that it becomes like a well-worn path to the throne of God. We walk it weekly, not in boredom, but in familiarity – the kind of familiarity that breeds love, not contempt. The liturgical phrases – “Lord have mercy,” “thanks be to God,” “lift up your hearts” – sink into our bones. Far from stifling feeling, this frees us to feel the real weight of glory, the numinous awe of God’s presence, without the jarring clatter of trendy jargon or slang. Lewis once noted that modern people, ironically, might need to be “startled into reverence” by something that reminds them how un-ordinary God is. A fixed liturgy in elevated language can startle in just that way. Not by being bizarre, but by being beautiful and set apart. It creates “a space where personal feelings are only background to the drama of God’s being,” inviting us, as Scripture says, to “be still and know that I am God.”

In an age of casual irreverence, such stillness and holy speech feel almost otherworldly, and that is exactly the point. The liturgy is otherworldly, or rather it is of the coming world, the Kingdom breaking in. Or, in Klinean jargon, it is an eschatological intrusion.

Tolkien, Lewis’s great friend and the author of The Lord of the Rings, brought a similar sensibility from within Roman Catholicism. He loved the ancient Latin Mass with a passion. As the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s introduced modern languages into the Catholic Mass, Tolkien famously refused to give up the old tongue. His grandson recalls attending church with him after the switch to English:

“My Grandfather obviously didn’t agree with this and made all the responses very loudly in Latin while the rest of the congregation answered in English.”

Picture the old linguist in his pew, loudly replying “Et cum spiritu tuo” (“and with thy spirit”) even as others say “and also with you” – a lone voice of continuity. He wasn’t trying to be obstinate for obstinacy’s sake. Tolkien believed something vital was at stake, which was the beauty and reverence of the liturgy. In his view, many of the modern reforms were driven by a misguided chase after simplification and relevance.

In Middle-earth, Tolkien created languages for elves and men, crafting high speeches and common tongues. He understood that language has the power to carry the weight of myth and memory. Indeed, “In Rivendell,” he wrote, “there is memory of ancient things.” Likewise, he knew the Church’s language carries the weight of mystery and majesty. To discard such language, in his eyes, was not a gesture of progress but a severing of the Church from her living memory. It was like throwing a relic into the fire or, more hauntingly, like the destruction of Fangorn by Isengard, cutting down ancient trees to stoke the forges of modernity, letting the wisdom of the ages go up in smoke.

Both Lewis and Tolkien, in their imaginative worlds, portray the idea that certain words and modes of speech have power beyond the ordinary. Think of Lewis’s Narnia, where the great lion Aslan sings the world into being. Or Tolkien’s elves who speak in High Elven when matters of great importance or magic are at hand, switching to the Common Speech for daily business. These fictional details reflect a real truth. When we approach the Transcendent, we instinctively reach for a higher register. It might not be Elvish or King James English per se. It could be simply a tone of deep respect, a cadence that signals this is serious. We soften our voice in a cathedral, we stand a little straighter, we say “yes sir” or “yes ma’am.” We use words in church we might not use elsewhere – not to be fake, but to acknowledge the numinous reality before us. We are like children learning a new, solemn language to address our Father – “hallowed be Thy Name” teaches our tongue to show honor even as it makes our heart feel that honor.

Formed by the Language of Heaven

All of this leads to an important insight.

The language of the liturgy is not only for God’s ears, it is also for our souls. In His kindness, God gave us a liturgy patterned after heavenly worship precisely because we are prone to wander in the street – our minds pulled to and fro by the noise of commerce, news, and trivialities. The sacred speech of worship acts as a sanctifying agent, training us in holiness. As theologian James B. Jordan observed, “the liturgy is the way the world works.” By this he means that the rhythms and patterns of worship are a training ground for living in God’s world rightly ordered.

Peter Leithart echoes that the Church’s worship is not merely a reflection of our culture, but a formation of a new culture – a culture of heaven on earth. In the liturgy, week by week, we are jiggled out of the world’s mold and shaped into a people who speak Heaven’s language of faith, hope, and love. The Apostle Paul wrote that “our citizenship is in heaven.” Accordingly, when we gather on the Lord’s Day, we are like ambassadors stepping into our embassy. Inside that embassy, the motherland’s customs hold sway. We stand to hear the King’s edict (Scripture), we kneel in penitence, we rise to sing His anthem. We even speak with an accent of the age to come – an accent of reverence, joy, and deliberate beauty. This trains us so that when we go back out into the world, we carry that influence with us. We have spent time in the throne room, and the fragrance of that encounter clings to us, subtly affecting how we speak and act on Monday.

In early Christian worship, as described by St. Justin and others, believers would lift up prayers not only for themselves but for the whole world – prayers of intercession. They addressed God as “Lord, Almighty Father”, language that reminded them of His power and love. These acts were forming them internally. Modern observers have noted that what we say and do in liturgy sinks into our bones. It becomes part of us. If we spend an hour each week speaking to God as if He is holy and we are humble, we gradually become more humble, more aware of His holiness. If we sing rich poetry about God’s mercy, we find the concepts and even exact phrases coming to mind when we are later in crisis or temptation. In contrast, if worship were nothing but casual talk – “Hey God, what’s up” – our souls might never be lifted beyond the ceiling. We might leave worship with our vision no higher than when we came.

But give a congregation grand words to sing – “Crown Him with many crowns, the Lamb upon His throne” – and you give them a theology that expands their hearts. Give them a prayer like “Almighty and most merciful Father, we have erred and strayed like lost sheep” and you have taught them to locate themselves rightly before God as wandering children received by a merciful Father. The content of these prayers is scriptural, but the language delivers that content to both mind and heart in a way that a chatty paraphrase never could. It is far better than saying “Daddy God, I’ve been a bad boy or girl this week, and I need a pick me up.” It’s the difference between a piece of raw ore and a finely crafted chalice. Both contain the metal of truth, but one has been polished to shine.

Importantly, using a sacred register is not about making ourselves “holier” than others or erecting a barrier. It’s about elevating all of us toward God. It is inclusive in the truest sense. It invites rich and poor, scholar and dropout alike to grow into the language of Zion. Think of how children learn to speak. We don’t limit our vocabulary around them to baby talk. Rather, we speak the best we can, and the children reach up, grasping new words and meanings. In time, they become fluent adults.

So, it is with the language of the Church. A newcomer might not immediately grasp every term in the liturgy – “vouchsafe,” “adoration,” “covenant” – but by being immersed in it, week after week, and with discipleship, they learn. Their understanding deepens. Their spirit acclimates to the atmosphere of reverence. In fact, this is how sacred language has been handed down through history. The “holy, catholic Church” that we profess in the Creed didn’t get that phrasing by focus group or marketing strategy. It got it by tradition – by holy words being taught and received and then taught again. Such language makes us students of the saints. We speak as the apostles and church fathers and reformers taught us to speak, and in so doing we are tutored by them across time. We pick up their accent – which is ultimately the accent of Scripture itself. The Psalmist cried, “Worship the LORD in the beauty of holiness”. That phrase itself has come into many a liturgy. And it teaches: true worship should be beautiful and holy. The very sound of our prayers and praises should signal that “something special, something sacred is happening here”

Conclusion: Recovering the Language of Heaven

Before closing, I want to bring up the thoughtful question that inspired this essay: Wasn’t Jesus simple in His speech? Doesn’t the Gospel belong to the common man?

The answer, I believe, is yes—and yes, Jesus walked the dusty roads and spoke plainly to the crowds. Yes, the apostles wrote in Koine Greek, the language of the street. But this was not because the sacred required simplicity—it was because the Incarnation sanctifies even the common. Yet even then, there remained a distinction between the language of mission and the language of worship. Christ read the scroll of Isaiah in Hebrew. Paul quoted liturgical fragments with a poetic cadence in Greek. From the synagogue to the early Church, there was a recognition that the gathering of God’s people was not the marketplace, but the joining together of heaven and earth.

Liturgical language doesn’t diminish the beauty of the ordinary—it reveals the ordinary to be part of something extraordinary. We are not rejecting simplicity, rather we are refining it into clarity and reverence. And this is not elitism, but an invitation into training our tongues, like our hearts, to speak as citizens of another Kingdom.

We live in an age that has largely lost this sense of the sacred in language. Our ears are inundated with sales pitches, political slogans, and the constant informal chatter of digital media. In such an environment, recovering liturgical English (or any sacred vernacular) is not a retreat into nostalgia – it is an act of rebellion against the flattening of speech, indeed a sort of linguistic egalitarianism.

It is a way the Church can “be in the world but not of it,” to shine a light upward. We do not pursue an older style of worship language to pretend we’re in the 16th or 1st century. The goal is not archaic words for archaic words’ sake. As was wisely noted, there’s nothing magic about ‘Thou’ versus ‘You.’ The goal is to find words that best convey God’s glory and help conform us to Christ. When we say “Christ have mercy” using the Greek Kyrie eleison, we are consciously joining millions of voices through the centuries who prayed the same in their own times of need.

When we sing “Praise God, from whom all blessings flow,” we are borrowing the 17th-century doxology of Thomas Ken, which itself borrows from even older blessings. This layering of language is part of the richness of our inheritance. It is how the Heavenly Father beautifies His children’s speech – much as an earthly parent might teach a child to say “Thank you” properly, or to address elders as “Ma’am” or “Sir,” not to enforce classism but to instill respect and humility. So, God, through the Church, teaches us a gracious speech for addressing Him, full of thanksgivings and reverence.

Imagine a church where the language of liturgy has been entirely replaced with casual slang and hyper-modern idioms. It might feel easy and familiar at first—no “thees” and “thous” to stumble over. But soon, something crucial is lost: the sense that we have entered a different space—a holy time and place where God meets us. The words sound just like TV or Twitter. The vertical dimension flattens.

Conversely, when a church reintroduces time-tested liturgical words—whether in an older form of English or simply a more poetic, scriptural style—the atmosphere shifts. There is a hush, an attentiveness. I have seen it in our own church. The very syllables “Lift up your hearts” can lift up hearts, precisely because they signal: now we speak to the Lord of Hosts. In that moment, the sanctuary is connected to the courts of heaven.

We are not advocating that Christians must all use Shakespearean prose to pray. The issue is not dialect but register. It’s about using language intentionally set apart for God. Language that is reverent, beautiful, and true. In some communities, that might be a lofty form of their everyday tongue. In others it might mean retaining some classical phrases. Whatever the case, the principle stands: liturgy is not the street, because the liturgy is the doorstep of heaven.

When Moses approached the burning bush, God told him to take off his sandals. Today, when we approach God in worship, we take off the sandals of banality—those dusty, ordinary words and we put on the “clean shoes” of sacred speech (to adapt a metaphor from Lewis). We do this not to impress God (no one can impress Him with fancy talk), but to honor Him. And in honoring Him, we ourselves are changed. We really need to recover a theology of honor.

So let us recover our sacred language, our liturgical English or whatever form it takes in your tradition. Let’s rescue it from mere antiquarian interest and put it back to work in the service of the Kingdom. We undertake this not to build ourselves a tower of Babel, but to receive afresh the tongue of Pentecost—speech infused with the Holy Spirit and directed to the Father through the Son.

We will find that as we do, the cold, gray prose of a disenchanted world begins to glow again with color and meaning. We will see afresh that worship is indeed “serious business,” a joyous, transformative business.

In the liturgy, God patterns our speech after the speech of heaven. And as we faithfully speak and sing His praises in the loftiest language our hearts can offer, we are being fitted for eternity. Every “Amen” said with understanding, every “thanks be to God” uttered with gratitude, every “Alleluia” sung with joy, is like a small step up Jacob’s ladder, drawing us nearer to the full heavenly chorus.

The street will have its slang and clamor, and we will return to it to witness and serve, as Jesus did. But on the Lord’s Day, in the holy liturgy, our Lord bids us come up higher. Here we step into the throne room. Here we join with angels and archangels in language heavy with glory. Here our earthly tongues are schooled in the dialect of heaven.

Let us not be afraid or ashamed to sound a bit different from the street. For one day, the language of the sanctuary will become the language of the whole world, when “the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the LORD as the waters cover the sea.” Until that day, the Church’s liturgical speech serves as a beacon, shining with reflected light from that celestial city.

It invites all who hear, leave the din of the bazaar and enter the courts of the King.

"Casual worship" is a contradiction of terms. Properly speaking, it does not exist.

I greatly appreciate this series.