Welcome to The Narnian Digest! I’m feeling a little under the weather this week. With the changing seasons and the sinus issues that come with it, my head feels a bit discombobulated. I hope my writing isn’t discombobulated, but I’ll let you be the judges of that.

This week’s Digest is packed full of stuff. I hope you guys enjoy it!

Imagination as a Truth-Bearing Faculty

This week, I had the privilege of watching a captivating lecture delivered by Malcolm Guite at Nashotah House. For those unfamiliar with Guite, he is an Anglican poet, priest, and professor. In his thought-provoking discourse, he challenges prevailing notions of epistemology, asserting that imagination is not merely a creative impulse but a truth-bearing faculty. In some ways, it reminds me of Calvin speaking about the sensus divinitatis (the sense of divinity) which is a faculty that gives humans a knowledge of God.

Guite delves into the predicament posed by the Cartesian Divide, a conceptual framework that was popularized by Descartes. He highlights how, since Descartes, knowledge has been dichotomized into the realms of objective knowledge and subjective feeling. Since Descartes, subjective feeling is often stigmatized as individualistic, suspect, and inaccurate, while objective knowledge is perceived as entirely impersonal, devoid of personal values, and therefore deemed true. Descartes delineated two states of being, the res extensa (the external world) and the res cogitans (the internal world).

In essence, the res extensa encompasses everything "out there" that can be known objectively, while the res cogitans encompasses everything "internal" that is felt but eludes objective understanding. Guite astutely points out Descartes' relegation of God, angels, and the internal life of human beings to the res cogitans. This relegation, according to Guite, has contributed to the perception that discussions about God, angels, and expressions of inner life, such as those found in poetic arts, are inherently private matters. In effect, this relegation has marginalized these aspects, consigning them to a mere sideshow, overshadowed by the presumed centrality of objective knowledge found in the sciences.

Guite challenges the notion by pointing out that the objective knowledge thought to be found in the sciences aren’t so objective. To illustrate this, he shares a personal anecdote from his youth, recounting a day in a chemistry class at Cambridge. Assigned to draw conclusions from their experiments, Guite expressed his findings in the form of a prose poem. However, his unconventional approach was met with steaming disapproval from the chemistry professor, who admonished him for presenting conclusions subjectively, insisting on the exclusion of first-person singular pronouns and his flowery prose. To which Guite responded, “What do you want me to do? Present my conclusions as though I wasn’t present?”

Guite reflects on this incident as a moment of realization, recognizing a profound flaw in the prevailing mode of epistemology. The insistence on scientistic objectivity, he contends, is rooted in a fiction to eliminate the knower and their personal values. This, Guite asserts, is an inherently impossible endeavor.

Personally, I think Guite is onto something that is important. Whenever I look at the epistemology of the Bible, I see that we do not come to know things by becoming detached observers with no personal values, but by becoming participants in the thing being observed. The reality is that no one ever came to objectively know his wife or children by being a detached observer.

It's crucial to clarify that this stance should not be interpreted as an opposition to objective knowledge. Instead, it challenges the idea that Cartesian, disembodied, and valueless modes of knowledge should exclusively bear the mantle of truth. I have a multitude of thoughts on this matter, and I intend to delve deeper into it in upcoming writing endeavors. Exploring the insights of Esther Meek has been on my agenda, and perhaps in the New Year, I'll embark on a journey to re-enchant epistemology through my work.

The Body of Demons: A Reflection

It’s pretty easy to see the enemy at work in the world right now. However, it’s harder to see him at work in our own lives.

All the way back in the Middle Ages, Saint Thomas made the astute observation that angels and devils do not have “bodies naturally united to them.” This is true. Just look around. When was the last time you just saw an angel or devil walking around? Probably not recently. . . Or maybe you did, and just didn’t know it because it’s way subtler than what you’d think.

Several centuries before Saint Thomas, Saint Anthony said that when we aim at at vice instead of virtue, we become a body for devils to walk around in the world.

Here’s how that works.

When we aim at vice and let our passions rule over us, we become participants in things we weren’t created for. We were made to be in communion with God. But, when we are prideful, greedy, lustful, envious, gluttonous, wrathful, and slothful we share communion with devils instead (1 Cor. 10:21). And don’t forget, Saint Paul warns those who are covenant members about this in Corinthians. It’s a reality. You certainly can’t be possessed by a devil if you’re a believer, but you can certainly let them influence you and let them cause havoc through your actions.

It is key, especially in the world we’re living in, that we become a self-disciplined, virtuous people; that we become people who are oriented upwards towards faith, love, hope, courage, justice, temperance, and prudence; that we become people who rule over ourselves instead of being ruled over.

If not, we might put on the right uniform, but we’re going to be fighting for the wrong team. Think about that and consider it.

“You will not find their [the demons] sins and iniquities revealed bodily, for they are not visible bodily. You should know that we are their bodies, and that our soul receives their wickedness, and when it has received them, then it reveals them through the body in which we dwell.” — Saint Anthony the Great, Letter 6, vv. 50-51

“The demon of anger . . . suggests images of our parents, friends, or kinsmen being gratuitously insulted . . . making us say or do something vicious . . . The demon of avarice . . . suggests that we should attach ourselves to the wealthy.” — Evagrius the Solitary, The Philokalia

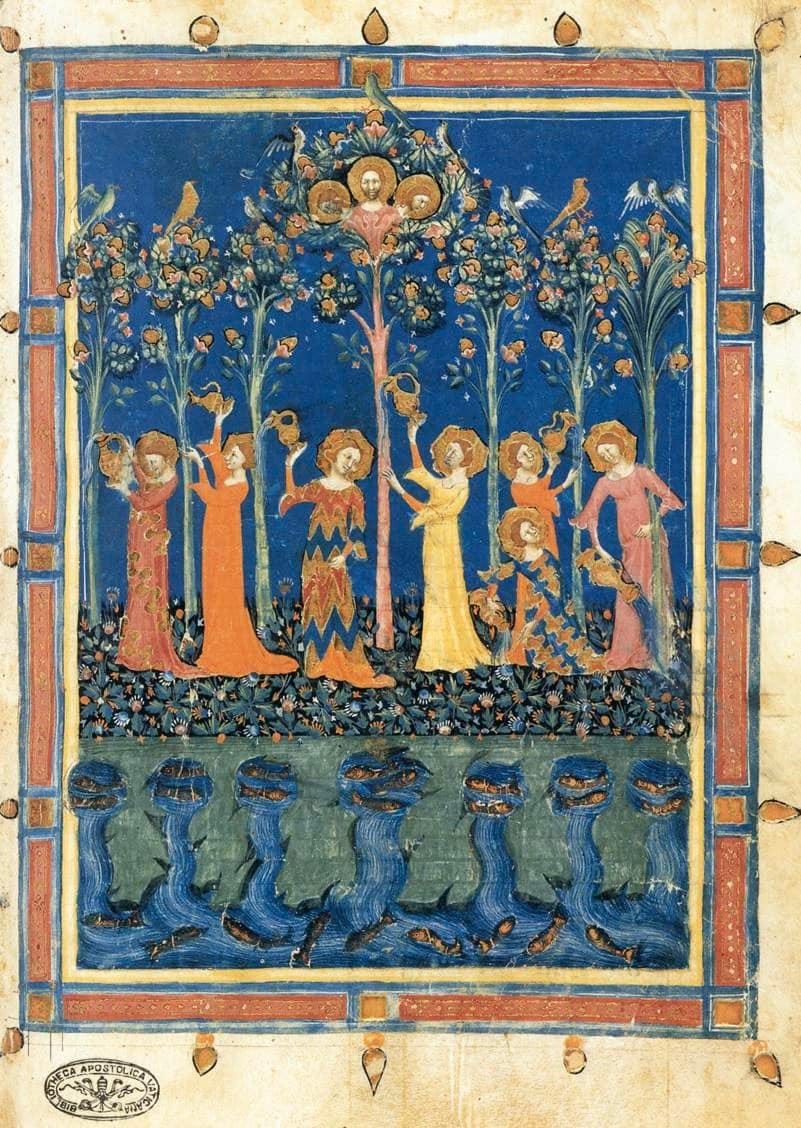

Crushed The Heads of Leviathan

A few Sundays back, I delivered a sermon at our church as part of our Gospel According to the Old Testament series, focusing on Psalm 74 and Genesis 1. The central theme of my message centered on the notion that Genesis 1-3 unfolds as a cyclical narrative. In Genesis 1, God initiates creation, brings order to chaos, and triumphs over the chaos serpent Leviathan (as depicted in Psalms 74). Moving to Genesis 2, God creates an image of Himself — someone who participates in the task of organizing the world's chaos and is destined to crush the serpent's head in Genesis 3. However, the man falls short, and this cyclical pattern echoes throughout the biblical narrative until the pivotal moment of Christ's incarnation.

Since sharing this sermon, I've received several encouraging messages from folks who found it helpful. I wanted to extend the opportunity to you as well, especially considering we're currently in the season of Advent. You can listen to it here.

The Theology Pugcast and Biblical Cryptids

In a recent episode of The Theology Pugcast, the discussion revolved around biblical cryptids — an area I've touched upon in my previous discussions. While those familiar with my past insights may find these topics recognizable, it's heartening to witness other reformational protestants now engaging in similar conversations. You can find that in the YouTube video above.

I’d like to do some more thinking on cryptids as Platonic Forms at some point. But that’s a topic and project for another time.

Full Proof Theology Podcast

Recently, I engaged in a discussion with Chase Davis from the Full Proof Theology Podcast regarding my book, Re-enchanting The Unseen: Angels, Demons, and Strange Beings from Time & Space. I had sent him a copy of the book for a class he was conducting at his church, focusing on topics like aliens. To my delight, he enjoyed the book and extended an invitation for me to join him on his podcast.

The conversation with Chase was both enjoyable and insightful. He has been doing commendable work delving into practical theology, and the questions posed during our discussion were thoughtfully oriented in that direction. I believe the dialogue will underscore the practical relevance of the book's content. Although the release date for the episode is uncertain, I will promptly share it in the upcoming Digest. Keep an eye out for it!

A Resource Roundup

To close out this week’s Narnian Digest, here are some publications and other things that I’m reading or listening to that I’ve found interesting.

- — Today, Hilary White from World of Hilarity shared an essay on the meaning of nativity scenes titled “What Does Your Nativity Scene Mean?” The essay is excellently crafted, and as the grandson of an Italian immigrant, I found the exploration of the nativity as an Italian tradition to be particularly fascinating. I highly recommend it to you.

— I stumbled upon a compelling piece by Morgoth on Morgoth's Review. Now, whether seeking advice from Morgoth (given his status as a fallen Valar) is a good idea is up for debate, but the article titled “A Brief Guide To Content Creation” is worth exploring. Especially for writers, it offers intriguing insights and tricks of the trade, including a mention of the dueling banjos.

- — Aaron Renn’s latest essay titled “Don’t Criticize Your In-Group in the Out-Group Forums” has some good advice. In this essay, Renn discusses that we can have ideas that are broadly right, but it’s possible to choose the wrong venue to express them. All this is going to do is give your enemy ammunition and reinforce the sense of superiority they already have. If you criticize your in-group in the out-group’s forum, using the value system of the out-group, don’t be surprised if you alienate a lot of people and receive a lot of hate in return.

The Hypostasis of the Archons: Platonic Forms as Angels by Marcus William Hunt — This week I read an academic journal from Marcus William Hunt of Concordia University Chicago on angels as Platonic Forms. It’s a fascinating read which makes the case that that the Platonic Forms are angels. Even if you read it and disagree, the read is very helpful and can help you understand concepts like forms, matter, participation, and how angels and demons exert influence in the world.