The May 2025 TIME cover features Remus, a revived dire wolf pup, under the red-struck word “Extinct,” signifying the reversal of the species’ fate. In our age, myth and science converge in the flesh of this creature, born not from an ancient forest but from a laboratory’s quest to resurrect what was lost. Colossal Biosciences, a biotech start-up, announced the birth of three dire wolf cubs – the first of their kind to walk the earth in over 10,000 years. Once mere legend, the dire wolf now lives again, its golden eyes meeting ours across time.

Resurrection of a Legend

Not since the last Ice Age has a dire wolf drawn breath. The very name “dire” comes from Latin dirus, meaning terrible, a fitting title for a predator that roamed from Canada to Patagonia before vanishing with the mammoths and mastodons. On an April morning in 2025, this Pleistocene specter stepped back into our world. In a secretive wild enclosure, pale wolf pups named Romulus and Remus tussle in the grass, while their infant sister Khaleesi learns to find her voice.

Though born of domestic dog surrogates, these pups are no dogs at all. They shun human touch, flinching and retreating even from the handlers who raised them. The wild blood of a lost world runs in their veins, untouched by the millennia that have turned wolves into pets.

How were these beings pulled from the realm of myth into life? The scientists at Colossal Biosciences – modern-day alchemists of genetics – deciphered the dire wolf’s genome and “rewrote” the DNA of a gray wolf to match it. Ancient DNA harvested from a 13,000-year-old tooth and a 72,000-year-old skull provided the genetic blueprint. Into the eggs of dogs, they implanted this reconstituted code of Aenocyon dirus, and in the womb of humble hounds the dire wolf was reborn, using the same cloning technique that once produced Dolly the sheep. The feat has been heralded as the first true “de-extinction,” though some scientists note that these creatures, 99% gray wolf with a few tweaked genes and polar-bear-like white fur, blur the line between resurrection and invention. Are they genuine dire wolves or genetic hybrids? Such questions do little to dampen the awe: after eons of silence, the terrible wolf of the Ice Age, that went extinct during the Younger Dryas, walks again.

Romulus, Remus, and the She-Wolf’s Legacy

It is no accident that the first two male pups have been named Romulus and Remus, after the twin founders of Rome who, according to legend, were suckled by a she-wolf’s mercy. The choice carries a poignant symmetry.

In the myth, a wolf gives life to orphaned human infants who would build an empire. In reality, it is humans (with a canine midwife) who give life back to an orphaned species of wolf. The Colossal team placed the engineered embryos into domestic dog mothers, one of whom nursed the newborn dire wolves for a few days. We’re reminded of that ancient bronze statue of the Capitoline Wolf, fangs bared and teats nourishing the infant Romulus and Remus – an icon of civilization’s dawn. Now the namesakes of those men nurtured by a wolf are wolves nurtured by men. Romulus and Remus live in a guarded wildlife refuge, frolicking under the sun of a world their kind never knew. Their very existence is a living metaphor, as if the old stories have come full circle.

The third pup, a female, bears the name Khaleesi, a nod to the modern mythos of Game of Thrones. In George R.R. Martin’s saga, direwolves prowled the edges of fantasy, symbols of a primordial bond between the human protagonists and the wild. Khaleesi is a title meaning “queen” in that fiction, evoking a powerful mother of dragons. By giving this pup the name, the scientists acknowledge our contemporary folklore. It’s a curious christening. Khaleesi was no direwolf in the story, yet here she stands as a bridge between fiction and reality.

In truth, George R.R. Martin himself is an investor in Colossal Biosciences. The author who enthroned direwolves in the imaginations of many has helped midwife their return to the real world, blurring the line between the tales we tell and the world we inhabit. In a promotional flourish, one of Colossal’s backers, film director Peter Jackson, even provided the actual Iron Throne (a prop he owned from the TV series) for a photoshoot with the living wolf pups perched upon it. The image of pale wolf cubs on that spiky throne of swords is startling: nature’s raw power seated on the artifices of fantasy. It’s as though the wolves of legend now rule over the realm of make-believe – a reminder that what was once only myth can bleed into reality.

Monsters at the Edge of the Map

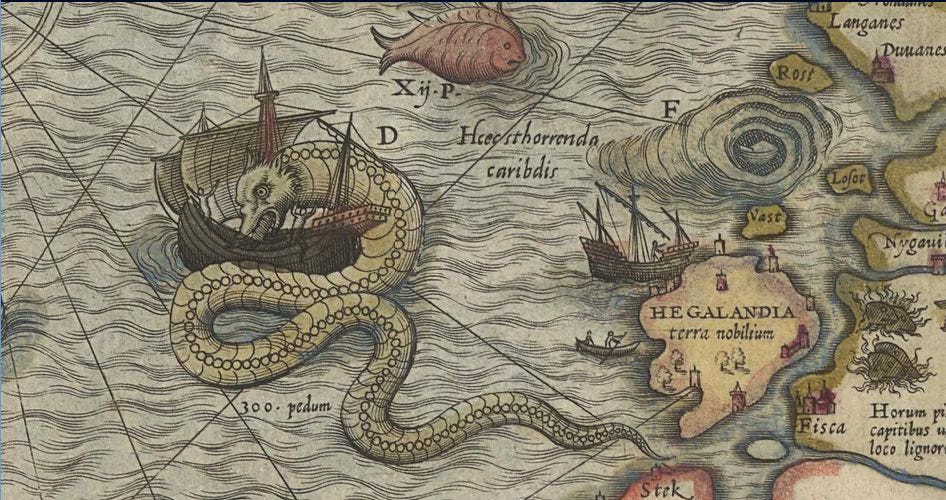

Our ancestors would not have been entirely surprised by strange beasts appearing at the margins of the known world. In medieval Europe, when mapmakers inked the unknown, they often filled the blanks with serpents, lions, and “here be monsters” warnings. Uncharted seas teemed with dragons and leviathans on those maps, marking the boundary between the familiar and the fantastic. “In that world, monsters could very well be real and were just part of the supernatural landscape,” as one historian notes.

A dire wolf resurrected in a genetics lab would have fit nicely in a bestiary of the world’s edge – an uncanny creature prowling the hazy border between what is and what should not be. Today, the edges of our maps are not in distant oceans but in the frontiers of science. The unknown stretches not over the horizon but in our laboratories and genomes, where new creatures are forged. The dire wolf cubs romp in a fenced sanctuary, but symbolically they inhabit that liminal space once reserved for mythic monsters: a place where ordinary folk fear to tread, beyond the safety of the village firelight.

Mythologies across cultures have long placed wolves and hybrids in portentous roles at the world’s end. In Norse legend it is foretold that the sun will be devoured by the great wolf Fenrir during Ragnarök, the twilight of the gods. Fenrir breaks his chains at the end of days, swallows the sun, and brings darkness before a new world emerges. To the Norse, the wolf embodied chaos at history’s furthest edge. One cannot help but think of Fenrir’s grin as we behold an Ice Age wolf brought into an age of climate tremors and ecological uncertainty.

From the Greek world comes the cautionary tale of King Lycaon, who in his arrogance served human flesh to Zeus. The king was immediately transformed into a wolf as divine punishment – a genesis of the word “lycanthropy.” In that story, the line between human and beast is crossed as a result of transgression and sacrilege.

Now, in our own age, we cross a new line: resurrecting beasts that God had consigned to eternity. Are we perhaps daring the same hubris that turned Lycaon into a monster? The Chimera of Greek myth which was part lion, goat, and serpent was slain by a hero, yet its name now lives on in our science to describe genetic hybrids. What medieval folk feared to find in distant lands, we are crafting with pipettes and code. The dire wolf itself is a kind of chimera of time – an ancient being brought forth through modern means, a hybrid of past and present. Standing at the world’s edge, these creatures provoke that old, tingling mixture of wonder and fear.

The Orcish Parallels and the Created Order

In J.R.R. Tolkien’s mythology, nothing truly new can be made by evil – living things can only be distorted. His Orcs were not a separate creation ex nihilo, but corrupted mockeries of Elves and Men. Tolkien described Orcs as a “distortion” of the beings that Eru (God) had originally made. They were bred in pits by dark powers, stripped of their beauty and turned into something foul. While the scientists at Colossal are no dark lords, the parallel is uneasy: here too we see life not created wholly anew but pieced together from the fragments of what was.

Is the new dire wolf a restoration of nature’s poetry, or a distortion of it? The motive matters. Tolkien’s dark breeders sought dominion and warfare; Colossal’s founders claim they seek discovery and even ecological healing. Yet even noble intentions must reckon with consequences. To some critics, reviving a long-extinct predator and keeping it penned on a refuge feels like playing at Morgoth’s work, reshaping life to our designs, potentially without the wisdom to foresee the results. “There’s a risk of death. There’s a risk of side effects that are severe… a lot of suffering… miscarriages,” warns one bioethicist of such de-extinction efforts.

Indeed, one of the dire wolf pups did not survive infancy, and the cloning process doubtless entailed failed embryos and lost pregnancies along the way. In Tolkien’s tales, attempts to bend life to one’s will often result in sorrow and cursed offspring. We might ask: what price will these creatures (and we, their makers) ultimately pay?

C.S. Lewis, too, wove warnings about the misuse of science into his fiction. In That Hideous Strength, the culmination of his cosmic trilogy, ambitious technocrats try to remake nature and even cheat death, egged on by dark spiritual forces.

Lewis portrays this as a grotesque violation of the created order, a literal bending of God’s design that invites destruction rather than redemption. The new dire wolves are not born of malice, yet they do represent our audacity in tampering with the boundaries of life and death. Lewis wrote of a moral law that modern man ignores at his peril, and of how the final conquest of Nature might end up being the conquest of man by his own devices. One can imagine Lewis looking at the spectacle of lab-made dire wolves and cautioning that just because we can do a thing, does not mean we ought to do it.

Even Ben Lamm, the CEO of Colossal, acknowledges the “playing God” aspect. “Every time we cut down the rainforest or overfish the ocean, we are playing God on some level… We humans are very good at changing the natural flow of things,” Lamm said in defense of his project. In his view, bringing back an extinct wolf is a “moral imperative” to atone for extinctions we caused and to bolster endangered ecosystems. Yet, Lewis’s spiritual cosmology reminds us that bending the pillars of creation is a grave act. To wrench an entire species out of the void of extinction is to reach into a domain that our ancestors left to God and providence. It requires humility as much as boldness. Without a guiding wisdom, our cleverness can quickly become “the abolition of Man,” and of wolf, and of wonder.

Twilight of an Age

On a quiet preserve, behind fences meant to tame the wild, a dire wolf lifts its muzzle to the wind. Its nose tastes a world unlike the one it was meant for, a sky not its own. Yet it lives, and that fact alone should shake us. This creature is not merely a curiosity of science. Rather, it is a signpost. It is a marker that we have crossed a boundary, passed through the veil, and stumbled into an epoch not unlike the days before the Flood, when men summoned things into the world that should not have been. The strange flesh of hybrids walked the earth then, too; birthed from transgression, baptized in violence, and judged by water.

We live, now, at such a threshold. Not merely the twilight of an age, but the dimming of the old sun, the slow collapse of the created order under the weight of our tinkering. The “end of the world” is not always heralded by thunder and meteors. Sometimes it arrives quietly, through a synthetic womb. We are not at the end of history, but we are at the end of a certain kind of world; a world where the distinction between the living and the extinct still held sway.

This resurrection is not just the return of an animal. It is the return of a way of thinking that believes nothing is truly forbidden. The dire wolf stands, not as an innocent marvel, but as a chimera of human pride and ancient memory. Its presence is a wound in the fabric of the world; a tear where space gives way, and time, ancient and ungoverned, comes spilling through. It is a fracture in the old enchantments, a breach in the deep magic that once held the wild things in their appointed bounds. And the naming of these pups, Romulus, Remus, Khaleesi, is no mere meaningless choice. They are names from fallen worlds, from civilizations that collapsed under their own glory. Names of empire, myth, blood, and fire. And now we give them to new beasts, as if to crown ourselves creators of our own legends.

Tolkien wrote that the great ages of the world end not in noise, but in sorrow and fading. Lewis showed us that when men lose the Tao, the moral order, they gain the world and lose their soul. What we see now is not merely the fruit of curiosity, but the fruit of power unmoored from wisdom. We have reached the monsters at the edge of the map, and we have invited them in. Not as enemies, but as trophies.

These wolves, born not of nature but of design, do not belong fully to the past or the future. They are echoes of the deep past, but their return is not a restoration. It is a transformation, or perhaps a transgression. We are not simply healing what was lost; we are rearranging the furniture of creation. We are drawing circles where God once drew lines.

And so, as we stand in the dusk of this present world, we must ask: What else will we resurrect? What else will we summon from the abyss of memory and death, cloaked in good intentions but animated by old desires? When the sons of God took wives from among men, giants walked the earth. In that age, judgment soon followed. Will we repeat the pattern?

The dire wolf’s howl is not just the sound of a returned predator. It is a prophetic voice, echoing from the edge of the world. It calls us to reckon with what we are becoming, and what we are leaving behind. It is, perhaps, the firstborn of a new age. But whether that age will be one of wonder or woe, blessing or curse, remains to be seen.

The twilight deepens. And the wolves have risen.

This is utterly brilliant.

I think your ability to infuse stories and myths into commentary is very refreshing when it comes to topics like this. I listened to a buddy talk about this for an hour this week, and all he could talk about was the "how" and the "what's next". I imagine that a lot of cultural commentators would focus on similar things. And if they did touch on the "why" or "what this means", it would be on sociological or political terms, not narrative ones. Quite the way to start my Friday, hahaha.