Introduction

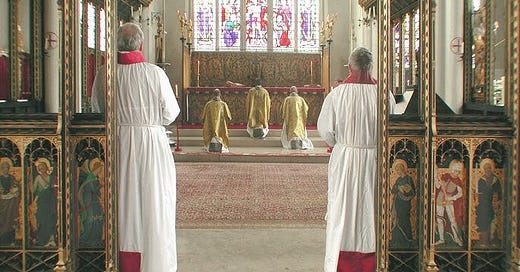

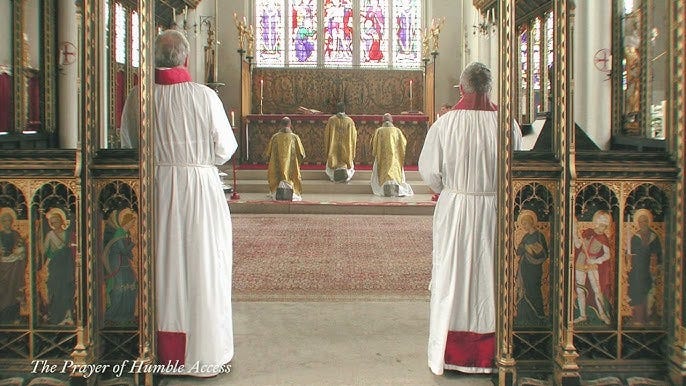

This Sunday, I’m preaching on the liturgy.

We are midway through Lent, that holy season in which the Church walks barefoot through the dust, her eyes cast not down in despair but lifted toward Jerusalem. Each sermon during this season has sought to draw our gaze to the mystery of worship and formation—that strange process by which sinners are…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Narnian to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.